This is Part Three of a four-part series about the development of doctrine. Here’s parts One and Two.

This whole section draws largely from All Oppression Shall Cease: A History of Slavery, Abolitionism, and the Catholic Church by Fr. Christopher Kellerman, SJ. (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2022).

A historical case study

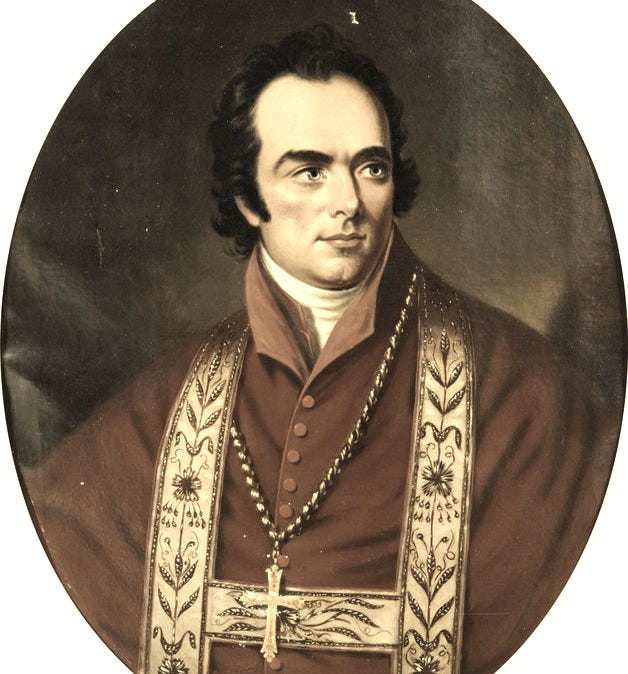

In 1840, Bishop John England—the first bishop of Charleston, South Carolina—wrote a series of letters to John Forsyth, the US Secretary of State at the time. Forsyth had been publicly claiming that Pope Gregory XVI had condemned slavery in his 1839 Papal Bull In Supremo Apostolatus. Bishop England felt the need to correct the Secretary of State because Pope Gregory had not in fact condemned slavery itself, only the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

In the course of his letters, Bishop England drew from Scripture, Tradition, the natural law, and multiple historical examples of the Church tolerating and engaging in slavery to argue that slavery itself was not immoral and that the pope has no authority to teach otherwise.

As surprising as this may be for Catholics to hear now, Bishop England’s analysis of the Church’s teaching on slavery was not off base. Slavery was widely practiced by the patriarchs in the Old Testament, was never condemned by Jesus, and St. Paul famously tells slaves to “be obedient to your human masters with fear and trembling, in sincerity of heart, as to Christ” (Eph 6:5).

The Didache repeats this exhortation of obedience and many Church Fathers—including St. Ignatius of Antioch, St. Augustine, St. John Chrysostom, St. Basil, and St. Gregory of Nazianzus (the latter two personally owned slaves)—did not view slavery as incompatible with Christianity. Pope Gregory the Great defended slavery and also owned slaves, including children. At least four ecumenical councils explicitly permitted slavery and St.Thomas Aquinas taught that slavery was not against the natural law. Christians advocating for the total abolition of slavery were in the extreme minority throughout the patristic and medieval eras.

Slavery was still present in the Church as it moved into the Renaissance. For example, in 1452, as European countries were beginning to explore and colonize Africa, Pope Nicholas V promulgated the Papal Bull, Dum Diversas granting the King of Portugal explicit permission to “invade, conquer, fight, subjugate the Saracens and pagans, and other infidels” and to “lead their persons in perpetual servitude.” This effectively gave the Portuguese full license to enslave Africans.

Then in the next century, Pope Paul III, even though he explicitly allowed Christians in Rome to purchase slaves, condemned the enslavement of the Indigenous peoples in the Americas by the Spanish. At this time, theologians, canonists, and popes were not arguing about whether or not slavery was evil, but in what circumstances it was or was not allowed. It was not until Pope Gregory XVI’s papal bull in 1839—after tens of millions of Africans were enslaved—that the Church publicly condemned the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

So, in 1840, Bishop John England was on solid doctrinal ground when he said that slavery itself was not immoral. In fact, in 1866, twenty-six years after the bishop’s letters, the Holy Office (now called the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith) taught, with the approval of Pope Pius IX, that slavery “considered in itself and all alone, is by no means repugnant to the natural and divine law.”

Then, in 1888, despite the weight of Scriptural justification and 1800 years of Church teaching and engagement in slavery, Pope Leo XIII taught, “the condition of slavery, in which a considerable part of the great human family has been sunk in squalor and affliction now for many centuries, is deeply to be deplored; for the system is one which is wholly opposed to that which was originally ordained by God and by nature” (In Plurimis 3). Pope Leo repeated his condemnation of slavery in his 1890 encyclical Catholicae Ecclesiae. The Church has repeatedly condemned slavery since then. Most notably, the fathers of the Second Vatican Council said slavery “insults human dignity” (GS 27) and then in his 1993 encyclical Veritatis Splendor, Pope John Paul II taught that slavery is intrinsically evil.

There are a few things worth noting about the history of the Church’s teaching on slavery. First, an action that was repeatedly encouraged and allowed by the Magisterium and explicitly taught as not “repugnant to the natural and divine law” is now understood as intrinsically evil. The more developed “butterfly” of Pope John Paul II’s teaching about the dignity of every human person looks nothing like the “caterpillar” of Pope Pius IX’s understanding of human dignity. This development ultimately led to nothing less than a reversal of the Church’s teaching about the morality of slavery. History demonstrates the possibility of dramatic change in magisterial teaching.

Second, while Pope Francis explained that his development of the Church's teaching regarding the death penalty centers primarily on the Church’s greater understanding and awareness of the dignity of every human life, Pope Leo XIII did not provide an explanation for his development concerning slavery. While his teaching emphasized Christ as the great liberator and the fraternity of all people, Pope Leo also engaged in a revisionist history to justify his development, claiming the Church has always desired to end slavery, even erroneously stating that “the Roman Pontiffs, who have always acted, as history truly relates, as the protectors of the weak and helpers of the oppressed, have done their best for slaves” (In Plurimis 13).

Looking back on those historical teachings through the Church’s present teaching, we could say that Pope Leo XIII’s development regarding slavery was also the result of the Church growing in her understanding of human dignity. We can conclude now that the “perennial substance” (to borrow Pope Francis’s terminology) of the Bible’s passages about slavery does not include slavery itself and the many examples and justifications of slavery in the Scripture and Tradition are products of cultural conditioning. By condemning slavery, Pope Leo XIII recovered a deeper “patrimony of the Church” and was “in full harmony with the teaching of Jesus himself” (to borrow Pope Benedict XVI’s terminology).

Third, it is easy to hear echoes of Archbishop Lefebvre and Cardinal Burke in Bishop England’s letters. Specifically, regarding the pope’s ability to condemn slavery, Bishop England wrote:

“…the Pope is the divinely constituted and authorized witness of the doctrine and morality of the unchanging church, and not a despot who can alter that teaching at his mere will; whilst the church herself claims no power either to add to the deposit of faith, or to change the principles of that morality for whose promulgation she is divinely commissioned.”

This exact argument, almost verbatim, has been repeated by critics of Pope Francis’s magisterial teaching. In fact, in a 2014 interview, Cardinal Burke said, “The pope is not free to change the church's teachings with regard to the immorality of homosexual acts or the insolubility of marriage or any other doctrine of the faith” (emphasis mine). It is clear by now that the assertion that the living Magisterium has no authority to change the Church’s teaching reflects neither history nor the Magisterium's understanding of its own authority.

Finally, the dramatic change in the Church’s teaching on slavery raises some challenging questions about the role of the faithful when we believe that a teaching needs to change. Can 15th century Catholic abolitionists be seen as unfaithful to the Church’s teaching when they were being faithful to what the Church would eventually teach in the 19th century? If the Church’s teaching can dramatically change, then it follows that unfaithfulness in one era could be faithfulness in the next. What does that mean for Catholics who are opposed to some of the Church’s moral teachings now?

There are not easy answers to these questions. Navigating what this means for us personally will require a well formed conscience and an active and personal relationship with a God who we know is good. Is it a coincidence that St. John Henry Newman, the theologian who the Fathers of Vatican II drew on to understand development of doctrine, is also who they referenced for their teaching on conscience? While the relationship between personal conscience and Church authority is beyond the scope of this article, perhaps, as each of us navigates this tension, we ought to recall Newman’s saying, “I shall drink to the Pope, if you please, still, to conscience first, and to the Pope afterwards.”

Look out for the fourth and final post in this series where we will take everything discussed so far and apply it to the ongoing Synod on Synodality.