I wanted to dive a little deeper into one of the points I made in my post two weeks ago about the vision of this substack.

In it I explained how I see the teachings of Pope Francis as so important for a the Church today. Drawing from a speech by Bishop Barron, I specifically juxtaposed Francis’s teachings with the Catholicism I was taught from the generation before me.

A couple of years ago, a theologian—who I both respect and am critical of—wrote an article commenting on the state of moral theology in the Church today. The author criticized theologians and pastors who set the bar too low for Christians who, he rightly points out, are called to nothing less than heroic sainthood.

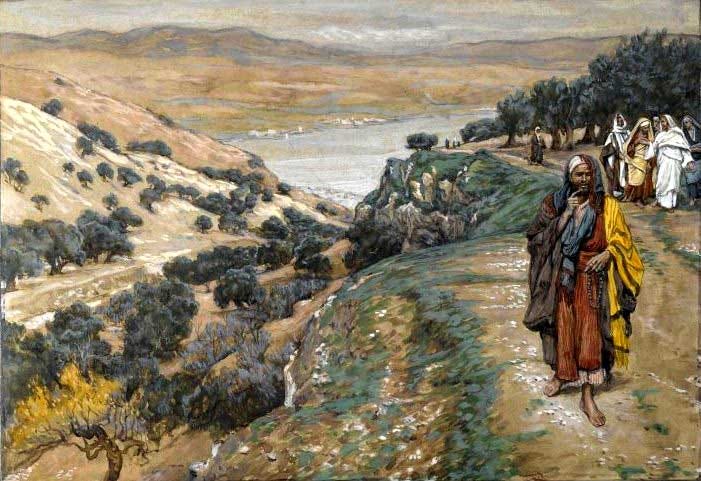

He used the story of the Rich Young Man as the setting to juxtapose two different versions of morality, more than that, two different versions of Christ.

The first version of Christ, the commentator proposes sarcastically, says to the young man, “Hey dude, it is okay. Don’t worry. Chill. Just do the best you can in the complex circumstances of your life, give to God what you most generously can at the present moment within the confines of those circumstances, and God will accept it. And you can have a certain peaceful conscience about it all.” This is a “you do you” Jesus who does not make any real demands on the lives of his followers.

The second version of Christ—which the author proposes is the true version—just bluntly tells the young man that his wealth is a problem and then shakes the dust from his feet when the young man walks away sad. This is a “facts don’t care about your feelings” Jesus who makes high demands and allows us to walk away if we think it’s too difficult.

I would like to propose that both of these pictures of Christ are more caricatures than they are the real portraits of Christ.

In Mark’s recounting of this story, before Jesus tells the young man to sell his possessions, he looks at the man and loves him (Mark 10:21). This is not a tough love Jesus, this is Mercy Incarnate.

Further, as Monica Pope, a mentor and catechist has pointed out to me, some traditions in the Church propose that the mysterious young man who followed Jesus after he was arrested in the garden wearing nothing but a linen cloth (see Mark 14:51-52) is in fact the rich young man. Between the day he left Christ sad because of his own weakness and attachments and the day of the Lord’s agony in the garden, the young man had indeed sold everything and followed Jesus.

Christ didn’t let this man walk away, he was just patient with him. And patience should not be mistaken for leniency or complacency.

The call to go to the heights of heroic sanctity AND the recognition that holiness is a process of growth that happens in time and can be marked by times of weakness are not competing ideas. They can both be true. As Pope Francis teaches:

“We can wonder if God is demanding too much of us, asking for a decision which we are not yet prepared to make. This leads many people to stop taking pleasure in the encounter with God’s word; but this would mean forgetting that no one is more patient than God our Father, that no one is more understanding and willing to wait. He always invites us to take a step forward, but does not demand a full response if we are not yet ready. He simply asks that we sincerely look at our life and present ourselves honestly before him, and that we be willing to continue to grow, asking from him what we ourselves cannot as yet achieve (Evangelii Gaudium 153).

That initial article spoke of accompaniment and discernment as merely a “word salad of meaningless buzzwords” that masks the belief that “holiness is not for ordinary people.” Perhaps some theologians or pastors are misusing that vocabulary. But that’s no reason to throw the baby out with the bathwater and prop up a caricature of tough love Jesus.

And here’s where I get to Bishop Barron. In 2018, during a talk he gave at the World Meeting of Families in Ireland, Barron clarified what he saw as the mission of Pope Francis by comparing his teaching with what he saw in the seminarians he helped while he was rector at Mundelein Seminary. He said:

“The shadow side of the John Paul II generation of seminarians was they often got deeply frustrated when they fell short of the ideal. You know because he [John Paul II] was such a heroic figure (indeed he was) and held out such a heroic ideal (indeed he did), and they properly were called to follow it. But then what do you do when you fail? I think they struggled with that. And I read Francis as being sensitive to that fact, that part of our pastoral experience. What do we do when people fail? And he prefers the path of mercy and reinstatement to the path of exclusion. And I think that strikes me as right.”

I believe Bishop Barron is correct here. And I would add patience and accompaniment to mercy and reinstatement.

In the spiritual formation I received from the JPII Generation there was a tendency to see the Church and her moral teachings in a defensive way, as a wall separating us from the immorality “out there.” This created rigid boundaries—often using sexual morality or partisan politics—about who is in or out, who belongs and who doesn’t. Protection and purity were prioritized over reinstatement and accompaniment, distorting who God is and breeding an environment fertile for spiritual abuse.

God is not unconcerned or lenient with our behavior, but neither does he simply lay down the gauntlet and let us walk away from him if we’re not man enough to take up our cross at that very moment. Jesus didn’t shun the rich young man from the community or from his loving gaze, in fact, God told us that he is a shepherd who chases each and every one of us down and does not stop until he finds us (Luke 15:4). God meets us in our weakness and patiently heals us, making us more free to follow Him.

This is just what I needed to read today. Thanks!